Reinforcement Learning

Introduction

Deep Q-Network, abbrievated as DQN, is a reinforcement learning method first proposed by DeepMind where a convolution neural network is trained using Q-Learning. Q-Learning (q for quality) is a reinforcement learning algorithm that tries to learn the “quality” of the next action in terms of maximizing future rewards. Ideally, we reward the agent for every step that it takes so that it can better understand which moves were for the better or worse. The rewards can vary depending on a variety of factors such as current environment, time surpassed, the preceding environment etc. and the goal is to have the agent learn what happens in between starting and “finishing” a game or completing a quest.DQN provides advantages over traditional unstable neural network learning through techniques such as target network, experience replay, and frame skipping and stacking.

Target Network

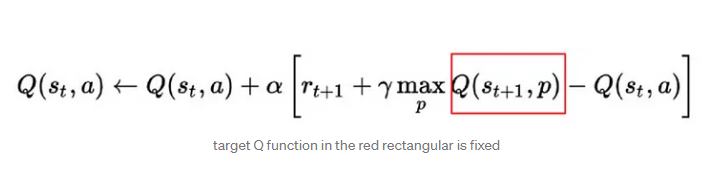

The difference between DQN and simple Q-learning is that with DQN, we are updating many state/action values at each timestep as opposed to just one update in Q-learning. Q-learning uses an exact value function whereas DQN uses a function approximator. This multiple updating in DQN can cause proximate action values which would be stable in Q-learning to be affected. During updating we use a target network (described in the original paper as Q-Network) which allows for the parametes of the target function to be fixed with the network of latest steps.

Without the target network, the learning would become unstable as instead of updating on ‘p’ (as shown in the figure above), we would instead be relying on ‘a’ for both the target and the prediction. This would cause the two to not be independent and can often result in what is called ‘catastrophic forgetting’. The underlying idea of using a target network is to allow the system to build upon previous experience and successes.

Experience Replay

Experience replay is the first step to address the overfitting which can occur in traditional deep neural networks. Experience replay stores experiences (states and the actions taken) and makes mini-batches to update neural networks. This not only increases efficiency through the reuse of previous samples and learning speed through mini-batches, but also allows for increased stability of the learning process by reducing correlation between experiences to break the temporal relationships of the neural network learning updates.

Frame Skipping and Stacking

Frame skipping and stacking is a rather confusing subject which is not all so clearly explained in the original paper. In the original paper, both values are equal to 4 which can throw some readers off. The main idea is that the learning environment used ALE allows for simulating Atari games at 60 frames per second. Stacking and frame skipping is combined in order to not only gain more information, but also to reduce computational costs. The idea behind this is that the games require information about things like motion which occur over a period of time (such as how the ball moves in Pong). By taking batches of 4 consecutive frames (ie. the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th frames) and stacking them together, we get a new state ‘s1’ which comes from (‘x1’, ‘x2’, ‘x3’, ‘x4’) making the input data dimension (4, 84, 84). As a result, the agent only takes an action on the last frame (ie. the 4th frame). But, this selected action is repeated 4 times (due to the nature of skipped frames). The stacking and frame skipping parameters do not need to equal each other. We could just as well stack only two frames or skip every three frames.

DDQN

DQN at its core is Q-learning with a neural network policy and some tricks. DQN is often overoptimistic and overestimates as the max operator uses the same values to both select and to evaluate an action.

DDQN, double DQN, solves some of these problems of iterrelated values by using two separate networks for continuous updating and for referring target values. This separation is particularly useful for states where actions do not affect the environment in any meaningful way.

Some Results

I played around with a standard DQN setup on the Breakout. For purposes of reinforcement learning, Breakout is a very ideal game to start off with as there are only four actions; DO NOTHING, FIRE, (MOVE) RIGHT, (MOVE) LEFT. If we apply another “trick” such as making the rendering black-white and cropping the top off, we can further allow the agent to learn/focus upon precise paddle movement.

The original paper denotes one epoch as 50000 minibatch weights updates or roughly 30 minutes of training time and achieves around 150 score after 50 epoches although scores vary drastically. For my graph above, one epoch is representative of one game (5 lives and roughly 500 steps to start off) and is much shorter than an epoch described in the paper. For adventurous individuals who intend to give this topic their own shot, be warned that I spent over ten hours in training on a GPU.

Below is a similar graph for DDQN. Notice that after around 1600 episodes, the DDQN score is over twice that of the DQN graph and still on an upwards trajectory.

Here is a short demonstration of a sample game from the DDQN agent after 1600 episodes. We will observe that the agent begins to show some understanding of the game and is able to move the paddle to hit the ball upwards.

Below is another harder game from the ALE system. The Phoenix game allows for 8 total actions and the environment introduces more variables such as enemies moving and shooting projectiles. One of the benefits of training on Breakout is that the bricks at the top stay relatively consistent. Learning a game like Phoenix forces the agent to truly understand what is going on between each input image and interpret a correct action to undertake.

Some Conclusions

A favorite quote of chess GM Benjamin Finegold is “Tricks are for kids”. At least in terms of chess, I agree with this statement; a better play should simply have a better understanding of position and tactics. However, in the area of computer science, tricks are a necessity. Algorithms and the theory behind them often break down in practice and tricks are often required to obtain promising results. DQN can achieve and even surpass human-level gameplay in certain Atari games but struggles in other ones.

Q-Learning is an old idea first introduced in 1989 by Watkins in his PhD thesis and yet still has many problems to tackle. Unlike our Deep Mind Atari simulations, real life reinforcement learning in robotics cannot afford to “die” endlessly or even explore millions and billions of steps. The batteries die out quickly and learning must be completed in a few thousand steps. More importantly, Q-Learning has three quintessential issues of being a bootstrap procedure with delayed feedback, having an off policy algorithm which can cause diversion on even small finite state problems, and function approximation and its generalization is weak at best. Q-Learning needs these tricks like the ones above to produce favorable results but they are not the end-all solution.

For individuals interested in attempts to address these problems, papers such as this one by Liu are a good place to start. The tricks mentioned above are just ways to keep vanilla Q-learning working but lack the rigorous mathematical proofs as in Liu’s paper. Tricks are indeed for kids, but until we find a completely new alternate reinforcement learning path, Q-Learning and its tricks will have to suffice for now.